Your filesystem isn't just storage—it's the physical manifestation of how you think about your work. The way you organize directories reveals your mental models, shapes your creative process, and determines whether your projects become living systems or digital landfills.

The Hidden Cost of Chaos

Most people treat directory structure as an afterthought, creating folders reactively as needs arise. This produces the digital equivalent of a hoarding situation: scattered files, duplicates buried in forgotten corners, projects that exist in three different states across four different locations.

The real cost isn't just the time spent searching. It's the cognitive overhead of maintaining multiple mental maps, the creative paralysis when you can't find your previous work to build on it, and the quiet abandonment of projects that become too messy to navigate.

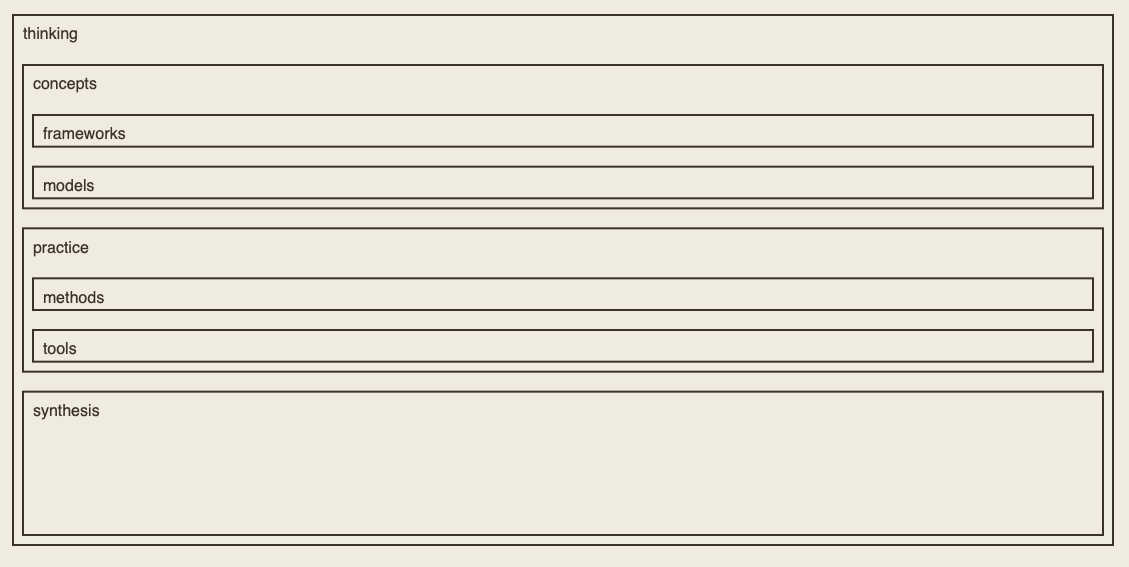

Structure as System Design

A well-designed directory structure operates as a system—a framework that guides behavior and enables emergence. Good systems make the right actions easy and wrong actions difficult. They create patterns that persist even when memory fails.

Consider the difference between organizing by file type versus by domain. A structure like Documents/Word Files and Documents/PDFs forces you to remember what format something was saved in. But organizing by domain—Audio/Projects, Audio/Samples, Audio/Documentation—mirrors how you actually think about and use the content.

The structure should map to your workflow, not to arbitrary technical categories. If you work on music production, your directories might flow from ideation to production to distribution: Ideas, Works-in-Progress, Rendered, Released. Each folder becomes a stage in your creative pipeline.

The Principle of Least Surprise

The best directory structures follow the principle of least surprise: when you need something, it should be exactly where you expect it to be. This isn't about rigid rules—it's about consistency with your own mental models.

This means your structure should answer natural questions:

- "Where would I look for this if I forgot where I put it?"

- "If I revisit this project in six months, where will I expect to find components?"

- "What's the narrative arc from raw material to finished work?"

When structure aligns with intuition, navigation becomes automatic. You stop thinking about where things are and start thinking about what you're making.

Hierarchy as Constraint

Deep hierarchies create friction. Every nested folder is a decision point, a place where files get misplaced or abandoned. Shallow hierarchies reduce cognitive load but can lead to overcrowded root folders.

The sweet spot is typically 2-4 levels deep for most work. Enough structure to create meaningful categories, not so much that navigation becomes archaeology.

Consider these two approaches:

Deep hierarchy:

Projects/2024/Q4/December/Music/Ambient/Sketches/draft_003.wavBalanced hierarchy:

Audio/2024-12-ambient-sketches/draft_003.wavThe second approach uses naming conventions to flatten hierarchy while maintaining clarity. The date and project type live in the folder name rather than nested structure. Everything about this audio project lives in one place.

Naming as Documentation

Directory names are documentation. They should communicate purpose, not just content. Generic names like New Folder, Stuff, or Misc are surrender—admissions that you haven't defined what something is for.

Good names answer questions:

Audio-Samples-PercussionbeatsSounds2024-Client-ProjectsbeatsWorkLearning-SuperColliderbeatsCode Stuff

Dates in directory names create automatic chronology. When folders naturally sort by creation time, you can trace the evolution of your thinking without checking timestamps.

The Living Archive

Directory structure isn't static—it evolves with your practice. But evolution is different from chaos. The goal is to create structures that can grow without collapsing.

This means planning for scale from the beginning:

- Create archive directories for completed work before they're needed

- Establish clear boundaries between active and inactive projects

- Use consistent patterns that work whether you have five projects or fifty

A good test: if you multiply your current number of projects by ten, does your structure still make sense? If not, it won't scale.

Integration Over Isolation

Modern work spans tools and platforms. Your directory structure should assume integration, not isolation. Audio projects need documentation. Code projects generate visual output. Writing projects accumulate research materials.

This is where domain-based organization shines. Instead of siloing by tool or file type, group by creative domain. Your audio directory can contain:

Audio/

Projects/

Samples/

Documentation/

Max-Patches/

SuperCollider-Code/

Reference-Recordings/Everything audio-related lives together, regardless of format. When you're working on sound, you're in the Audio directory. The structure reflects how you work, not how the computer categorizes files.

Structure as Externalized Mind

Your directory structure is an externalized version of your mental filing system. When done well, it becomes a second brain—a reliable external memory that mirrors and supports your thinking.

This is why copying someone else's structure rarely works. Their mental models aren't your mental models. The optimal structure for a photographer isn't optimal for a programmer. The structure that worked when you were a student won't work when you're managing multiple client projects.

The question isn't "what's the best structure?" It's "what structure mirrors how I actually work?"

The Path Forward

Start with your domains—the distinct areas of practice or creation you engage with. These become your top-level folders. Within each domain, create structures that mirror your workflow from input to output.

Use naming conventions to encode metadata—dates, project types, status indicators. Let the names do the work that deep nesting tries to accomplish.

Build in separation between active work and archives. Make it easy to move projects from active to complete without destroying context.

And remember: the goal isn't perfection. It's a structure that reduces friction, supports your creative process, and makes it easy to find and build on your own work.

Your filesystem is the foundation of your digital practice. Build it intentionally, and everything else becomes easier.

.png)

.png)